What a big, bursting lasagna of a book Garibaldi M. Lapolla’s The Grand Gennaro is, full of the pleasures of a novel, old-school and plotty, slap-dash and hasty in places, but vibrant, alive, delicious—and over too soon. I’d put off reading it for years because I’d (foolishly) assumed Gennaro would be a tired old Central Casting G, but really he’s a complex and contradictory character, worthy of both pity and contempt.

First published in 1935, Grand Gennaro has all the marks of the kind of foundational Italian-American novel that should still be in easy circulation. For one, to use the kind of masculinist boxing metaphor Gore Vidal would hate, it beat out Pietro Di Donato’s Christ in Concrete to publication by four years. And I’d argue that it’s aged more gracefully than Christ in Concrete (which, lest I be misunderstood, is a book I love), maybe because Grand Gennaro doesn’t deal in the kind of poetic, passionate-young-man’s language that makes that novel, at times, creak like a barn door. For another, it takes in just about all of the issues an Italian immigrant of Gennaro’s era and class would likely have had to contend with. Aspects peculiar to that milieu, and in some cases that of the larger tide of immigration from Italy, show up on every page, sure as Gennaro lives in an ethnic ghetto/works as a rag-picker/is underestimated or lampooned by the Americani. The “problem” with the book, really—touched on a bit by Steven J. Belluscio in his rich, comprehensive introduction to the 2009 Rutgers University Press edition—is that Gennaro is no kind of hero. He’s a heel. He’s a rapist, a brute, a thief, a spaccone. The existence of such a character is a “bad fact” for Italian-American self-esteem, let alone self-creation.

The plot is more or less a rake’s progress. Gennaro Accuci, a poor, illiterate contadino, flees crushing debt in his native Calabria in the late nineteenth century (temporarily leaving behind his wife Rosaria and their three children) and emigrates to the U.S. to “make America,” a favorite refrain of the book. To do this Gennaro will resort to whatever guile and violence he must. His initial act of usurpation—stealing his friend Rocco’s business by beating the crap out of him—is so shameless that it takes a reader’s breath away. What also took this reader’s breath away was that Rocco’s first resort in trying to get his business back from Gennaro was through similar violence; there’s no question of recourse to the police or the law. I would imagine this is an index of how little protected an Italian peasant found himself to be in this new world, which is pretty well a hangover of his status in the old country. (The particularly Italian-American fatalism of this—What you gonna do?—will be familiar to those of us with memories of hand-wringing grandmothers). From there, Gennaro does indeed “make America,” shoving his way forward, grabbing what he wants, and trampling many in the process, including his sad wretch of a wife, Rosaria. He reinvents himself—The Grand Gennaro has a clear echo of The Great Gatsby—and is set to enjoy the spoils of his dirty dealing, including a new life with the ideal young Americanized Italian girl, Carmela, when his life is cut abruptly short. Like the bad guy in a post-Code Hollywood movie, Gennaro is made to pay for his sins.

The novel is divided into three parts, “Gennaro,” “Rosaria,” and “Carmela,” which feels a little arbitrary, since—contrary to what these divisions might suggest—Lapolla doesn’t limit his close third-person narration to these individual characters in their named sections, nor does each section always hold its focus on that character. In the middle part, particularly, Gennaro’s old-world appendage of a wife, Rosaria, whom the uncharitable reader might also consider the big drag that Gennaro makes her out to be, often disappears from the page. The ranging third person, however, is part of the book’s vitality: Lapolla frees himself to swoop in and out of various characters’ minds as the story unfolds. And so we’ll see the world through Gennaro’s eyes, then turn around and see Gennaro through another character’s eyes—a vantage that often confirms the worst about him, or shows the reader the kind of figure that Gennaro cuts to those outside his milieu.

As one example, early in the book, a sleazy music-hall proprietor called Fitzgibbons reaches out and gives an amused flick to Gennaro’s golden earrings—these much-remarked-on, integral part of Gennaro’s mythos of self, passed down from his grandfather and worn to signal the pride he takes in his roots, as well as a kind of provocation to Americans and assimilated Italians. Fitzgibbons calls Gennaro’s prized earrings “the Goddammest things” and Gennaro is immediately on his feet, ready for a fight. But Fitzgibbons isn’t concerned. To him, Gennaro is a bumpkin and an easy mark. Later, when the earrings are stolen by one of Fitzgibbons’ girls and Gennaro goes back to get them, he walks in on Fitzgibbons wearing the earrings and doing an impression of him: “Nobody he getta deesa eerings from me—me the big dago what no give the damn for Presidenta, Kinga, or big business man…” Gennaro puts out his hand and Fitzgibbons, sufficiently shamed to be caught in the act, surrenders the earrings. Gennaro strides over to the girl who stole them and slaps her across both cheeks. It’s awful and also very filmic, all of this—you can easily picture Paul Muni in the role of Tony Camonte dealing these quick, vicious blows, oiled hair flying.

Later, after Gennaro has been brutally beaten up himself, after he’s raised money for a new church for the Italian colony (both to memorialize his status in the community and atone for his sins), and after he’s changed enough that he is in some way genuinely penitent, the many images of his previous brutality are still fixed in the reader’s mind. Likely this is pretty basic to understand, but this struck me as key to establishing the complexity of a character like this: to give the reader enough access to a character’s inner life that she’s willing to hold that duality in her mind. I wasn’t prepared for the sympathy I felt for this rotter.

The secondary characters are, for the most part, colorful and textured. While some have little sub-Dickensian-type identifying tics, they’re still pretty solidly in the realist mode, and what could have been types are instead individuals with specific qualities and failings. The key characters belong to the Monterano and Dauri families, who move into Gennaro’s three-story house (grandly named The Parterre by the “solid German butcher with dubious notions of architecture” who built it). In Italy, Gennaro the peasant would have been invisible to the aristocratic Monteranos and middle-class Dauris, but in America, he’s the one with the money so now he’s got the upper hand. The playing out of these reversals of fortune provides much of the plot of the book: it’s as if Lapolla dropped all of these characters into a house and imagined what would happen once he closed the lid. Carmela, who the reader follows from girlhood into womanhood, is in particular sensitively drawn, transcending her role as love interest to become a character active and alive, full of agency. She goes from being a vicitimized girl forced into a hateful marriage of “honor”—porca miseria!—with Gennaro’s useless son Domenico, to a woman who knows her own mind. She’s also an entrepreneur, a businesswoman, which cannot have been too common for a daughter of the era. The complexity of her feelings for Gennaro also makes the book feel unusually multidimensional and generous. In an earlier era or on the other side of the Atlantic, perhaps, a man like Gennaro would have earned Carmela’s wholesale condemnation. Dickens would have hated the guy.

•

Lapolla’s prose is a delight. It’s pebbly, various, studded with Italian and Calabrian words and distinctive cadences, and has a certain heat that is at times almost operatic, with plenty of dialogue driving it all forward. Maybe the dialogue most of all is what has kept the book from dating—we’re in a vernacular of the moment, full of snap and velocity. (The sections of dialogue also have bits that show the reader what Gennaro sounds like to non-Italians; the version of him who talks to his young Jewish lover Dora says things like “You no like?”). The book has passages that romp, canter, gallop, and ones that slow and linger. I particularly loved the descriptions of Italian Harlem, with the richness of specificity such as the “occasional roar of the gas tanks,” those twin sentries that once stood between 110th and 111th streets. Sometimes we get scene-setting exposition, particularly at the start of some chapters, but it rarely feels belabored.

Reading the book, one can sense Lapolla’s pleasure in the writing of it. He’s here to tell a story, one with a clear trajectory, a beginning, middle, and end, very much rooted in a particular time and place. Does this, I wonder, contribute to making Grand Gennaro “old”? Beyond what I touched on above, what’s the thing about this novel that made it nearly vanish? Lesser books with villains as main characters have greater play. Is there too much plot? Is it too white-ethnic, and of a flavor that hasn’t the same currency that it once had? I mean to say, has this milieu so vanished that this novel feels like a relic? Does the very thing that made me go back and finally pick it up—its specificity to a people, a time, a place—make it seem too “narrow” to a reader who isn’t quite as interested to that people, time, place? Does it not achieve that chimerical quality, “universality”?

Because I have an unhealthy interest in such things, I dug around a bit to see what the contemporary reviews were like. What did I find? A sort of resounding meh. No one hated it. No one loved it.

In a soporific New York Times review of September 1, 1935, Fred T. Marsh doesn’t seem so much interested in the actual merits of the book as much as how it and Lapolla’s protagonist fit into the critic’s generalized context of contemporary realist fiction: Gennaro is but one from “the welter of novels of ‘the American scene.’” Marsh writes that “these many heroes, pioneers all, each after his kind, are for the most part as sound and faithfully created and accurately limned a body of representatives as any realistic literature ever boasted anywhere or at any time.” Not only is this a fairly meaningless string of vagaries—so attenuated as really to tell you nothing—Marsh suggests that Lapolla has actually fallen down on the job. His portrayal of Gennaro “fails to convince us as an individual.” And so, Marsh writes, Lapolla has switched mid-novel to write “a story-picture of a bit of Little Italy,” which makes “fascinating reading, although the picture is better than the story.”

While the review is lazy and tepid, it’s not exactly condescending—that will come from several other reviewers. In the Saturday Review’s brief piece of October 26, 1935, the reviewer (“A. C. B”) calls the book “a colorful novel of no particular depth” and writes:

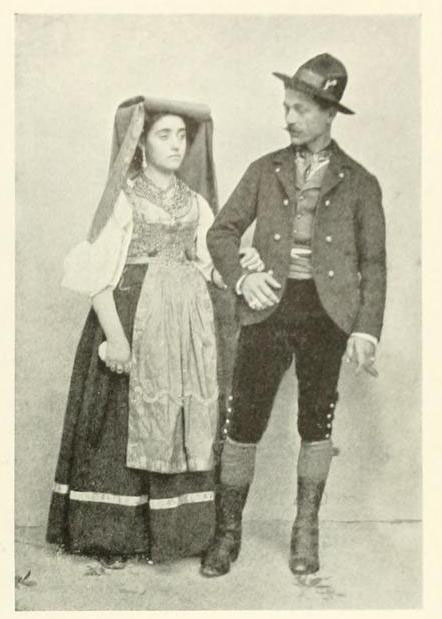

More successful with his background, Mr. Lapolla has contrived a convincing picture of the period as exemplified in this limited milieu; the processions, the feast-days, the family and social life of the Italian immigrant population glows with vivid colors. Here is their facile emotionalism; their quarrels spread over every page; their ambitions and their set-backs are presented in loving detail.

“Limited milieu,” “facile emotionalism”—those simple-minded, opera-lovin’ dagos! The editor of the Saturday Review at that time was Henry Seidel Canby, who wrote a nostalgic little memoir called The Age of Confidence about his golden years growing up in Wilmington, Delaware—indeed, in a grim piece of antiphrasis, his family lent its illustrious name to the dim neighborhood of row houses that I grew up in. Canby writes some awful things about “white ethnics” (“… the Irish who dug ditches and carried bricks up the scaffoldings of new houses, the Greeks in the fruit stands, and the Italians sweating on the embankments—they meant nothing to us, were only population”) but this cannot compare to the breathtakingly fucked-up things that Canby writes about Black people:

When they were sick or destitute we took care of them if they were our darkies, but of course what they thought, if they thought, and what they wanted, if they wanted more than we gave them, was not significant. They lived, naturally, in slums of their own, where it always smelled darky, and they were supposed to like it that way. Perhaps they did. Sometimes a “waiter” went “mean,” though not often, yet we were well aware that the savage in them was not entirely dead.

This, reader, was published in 1934.

In the November 1935 issue of the post-Mencken-era American Mercury, Frances C. Lamont Robbins, she of the Social Register, writes that Gennaro “should have lived in the spacious days of the Renaissance, for he was both ruthless and magnanimous; had energy, initiative, and imagination, combining, as only an Italian can, a capacity for cruelty with radiant amiability and childlike piety.”

These are all cases of the reviewer not being able to see beyond the construction of the Other—their critique stops there. The last contemporary review is, in theory, of a different nature. In what Fred Gardaphé calls “one of the earliest acts of indigenous Italian American criticism” (Italian Signs, American Streets: The Evolution of Italian American Narrative), Jerre Mangione, who would go on to write the beloved Mount Allegro, reviewed the novel for Malcolm Cowley’s New Republic.

So it’s strange to say, then, that Mangione’s is not a particularly sensitive review. It’s a little defensive, a little stingy. In a way it’s a photographic negative of the other reviews, those same concerns seen from the other side. Mangione comments on the dearth of Italians in American literature, and how they themselves—more correctly, Italian Americans—“have produced no outstanding writers of fiction and few novelists of any type.” However, “Mr. Lapolla is undoubtedly one of the best.” One of the best out of this tiny army of fleas? Faint praise indeed. Bizarrely, Mangione can’t be arsed to fact-check, and writes that Gennaro left Italy “wearing his grandmother’s earrings.” His main line of criticism seems to be that Lapolla’s Gennaro is too colorful, too large: “The author has a tendency to melodramatize his materials, to buy excitement at the cost of accuracy.” The review ends in a puddle as Mangione writes that Lapolla, who “hasn’t the emotional sensitiveness of a Harold [sic—he means Henry] Roth describing the Jews, or the dark-lensed photographic eye of a Farrell writing about the Irish,” still succeeds “in creating Italo-Americans who are vivid and alive and probably a novelty to the average person who, not knowing them intimately, is likely to draw his conclusions about them from the gangster movies.” So in its function as a corrective to the reigning stereotypes of Italian Americans, the book is better than nothing at all.

•

As I was wrapping up this piece, I realized I felt a certain lack of satisfaction with it. I was missing something in the book, some shadows running through its pages, some gestures not quite articulated. This sent me back to Robert Viscusi’s Buried Caesars, a key text of Italian American literary criticism and a book I find intriguingly personal and idiosyncratic.

Viscusi reading his poem, “An Oration Upon The Most Recent Death of Christopher Columbus.”

As Viscusi writes, the endgame of The Grand Gennaro begins when Gennaro surprises Carmela in an embrace with Emilio, Gennaro’s second son, in the hallway of the Parterre. In fact it’s the ruin of all of his dreams, in triplicate and neatly framed: the betrayal of his young and beautiful wife, the disloyalty of his best son, and the destruction of his home, his lares et penantes. Gennaro’s shock at this betrayal leads him to sleepwalk into his own death—a murder that he in fact predicts and maybe even welcomes.

It’s a mug’s game to play with fiction, but it struck me that Emilio is the author’s stand-in. Like Lapolla, he’s the family intellectual, the questioner. He’s gifted, restless. He’s the son who, like our author, goes on to college at Columbia—and there’s nothing like college to sever a second-generation immigrant from his old-country parents. Fascinatingly, in Leonard Covello’s ardent, generous memoir The Heart is the Teacher, we get a glimpse of Lapolla during his time at Columbia, or at least when he’s poised on the threshold of it. The scene was not what I might have expected. Covello writes that when he strides onto campus in September 1907:

I was immediately jolted from my idealistic conception of a university by a battle between the freshmen and sophomores. The campus tradition was that a freshman’s cap would be placed atop the flagpole. The sophomores would muster around the flagpole while our job as freshmen was to rush the pole and try to recover the cap. In this melee we punched and wrestled with each other until the upper classmen intervened, putting an end to the battle. We did not recover the cap and we were all pretty well roughed up on both sides. This was my introduction to Columbia. I remember limping from the campus with Garibaldi Lapolla, another East Harlem student who enrolled with me at the same time.

“Man alive!” Lapolla said, tucking in his torn shirt. “If the old folks could see us now! They’d think the whole bunch of us should be locked up in an asylum along with the professors and the dean.”

“Don’t tell them,” I advised. “Keep quiet.” Experience had taught both of us that the spreading chasm which separated us from our parents could never again be bridged and that what happened to us on the outside world belonged to us alone.

The “spreading chasm”—it sounds a little hellish, like a pit you could fall into and never climb out of. Covello was an educator, a role model, and in his memoir he sounds a relentlessly upbeat note. But from the harshness within the pages of The Grand Gennaro—particularly the bitterness of the young characters, including Emilio, over having been ripped from their families and sent to the Protestants to go through the chilly process of Americanization—I wonder how much Lapolla the young novelist had in common with Covello the optimist. I know little of Lapolla’s early life, so here’s more reckless conjecture: What if Gennaro’s death at the hands of the author Lapolla is something of a symbolic killing off of Lapolla’s real father? The father that needed to be killed, figuratively speaking, to allow the writer Lapolla to grow? A book like The Grand Gennaro was likely seen as a betrayal to the community. Was the killing actually incomplete in that the book didn’t find the success he had hoped for? Did that send Lapolla the writer of fiction into retreat? Make him penitent? Make him decisively take another path, like Covello’s, as an educator, and put the reckless ways of the novelist behind him?

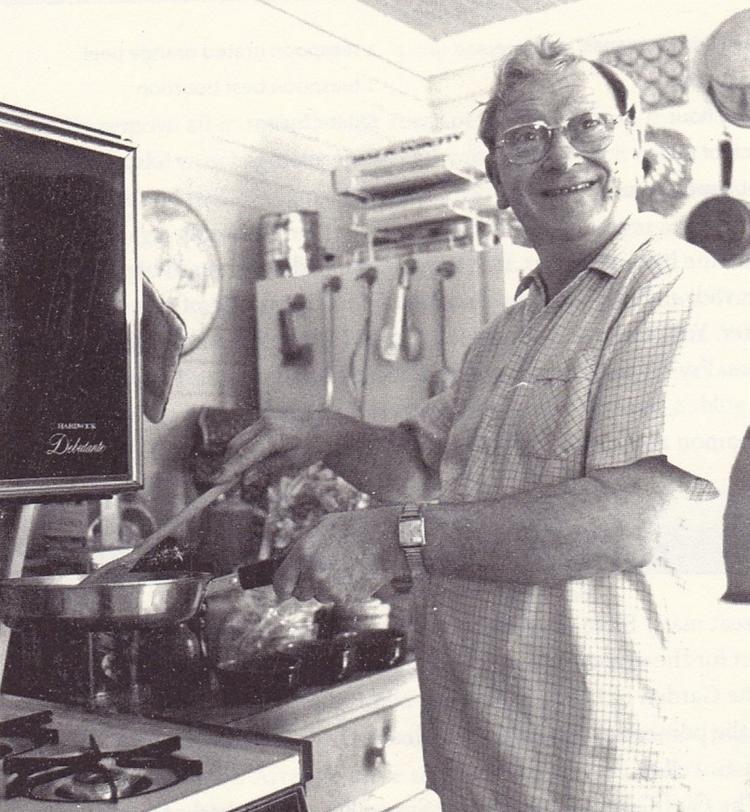

Because while The Grand Gennaro wasn’t the first novel that Lapolla published—Fire in the Flesh came out in 1931 and Miss Rollins in Love in 1932—it was his last. Lapolla’s longest career was not as a novelist but as a school principal, a role he held for more than twenty years. In 1953, the year of his retirement from the New York City public school system, Lapolla published two things: Italian Cooking for the American Kitchen and The Mushroom Cookbook. A year later, he was gone.

But how unfair of me to paint Lapolla’s story as tragedy. The man’s life was full to bursting. He married twice, raised a family, was a talented visual artist, served in WWI, (where he held “every position from buck private to cook to lecturer on personal prophylaxis to sergeant to lieutenant of artillery”), and knew his way around a kitchen. He was even on the angels’ side of history, defending teachers persecuted by HUAC, as Belluscio writes, “arguing that they should be judged not for their beliefs but, rather, for their ability in the classroom.” Indeed, in the one photo of an older Lapolla easily findable online, the one above—if you’ll forgive me this final bit of fancy—the man looks happy. Still I can’t help but think that if The Grand Gennaro had been understood for the achievement it is, Garibaldi Lapolla would have gone on to write more novels, acquiring greater skill along the way, and perhaps finally giving us a true masterpiece.

“What were you but a dream – a gentle dream/In the thoughts of your sleeping fate?”